Being a girl has always been dangerous.

When I was a girl I took a public school education — during which I was told that I would never amount to much — and turned it into the chance to go to a near-Ivy League college. And the man who decided he was better than my father told me that if I moved to that city, if I went to that school, that I would surely get raped. And when I got to that school, they gave me a whistle and told me to blow on it if someone ever tried it.

I never did.

Because, as it turned out, I was much safer on the south side of that city, surrounded by people I didn’t know at that school than I was in the house I grew up in. So safe, in fact, that I would often fall asleep on the stone steps of the little church at the heart of campus where alumni of the school often returned to marry one another. I fell asleep there not because I was drunk or on drugs but because I liked feeling like I could fall asleep outside, safe on the front steps of a big city, and no one would touch me.

I fell asleep on those church steps because sometimes, the people who say they are watching you walk home in the dark are waiting to see if you’ll fall into it.

But I’m not here to tell you about all that.

I’m here to tell you about how we hate girls now.

“We have been utterly possessed by girlhood,”

, a writer and cultural critic declares in a YouTube essay dissecting what they call the Girl-aissance.The girl-aissance, or girl renaissance is what they call the aesthetic and dialogic turn the Internet took towards conventions of girlhood in the summer of 2023. Girl Dinner; Girl Math; a girl billionaire going on tour and girls making friendship bracelets to trade at the show they had spent hundreds or thousands of dollars to attend. Girls talking about feminism in skirts that rode up to reveal their panties. Girls lining up in pink suits and dresses to watch films about the inception of atomic power and a doll back to back. But I’m Just a Girl. A grainy photograph of Paris Hilton, Britney Spears, and Lindsay Lohan crammed into the front seat of a car on a night out. Please I’m a star girls, silently screaming as they smile, smile!, for the audience.

The memes and the virality of girlhood were not, as Shaniya points out, cultural satire. Nor were they complete irony. Instead, something new was happening: an invitation with a wink and a nod, like when you show up at Disneyland the day before it shuts down due to a global pandemic. One last fun ride before everything changes, before the rug is pulled out from under, before the world you once knew fades away forever.

That was the Year of the Girl: an escape, however, temporary, back to something that could hurt you, could starve you, could will you to a slow deterioration under everyone’s watch. The Future is Female and Girlboss-style empowerment of the 2010s had given way to girls just wanting to have some fun one last time.

When I joined Substack — which felt similar to when I was a girl and joined other digital platforms that promised me that I could write and it would be seen by thousands of people (LiveJournal, Xanga, MySpace which, yes, had a blogging feature) — there were girls on here writing essays about their lives. And then there was a counter wave of girls writing essays about the girls writing essays about their lives (“girlhood essays”). And those girls had some very good criticisms about girlhood itself.

As a set of aesthetic conventions, girlhood is overwhelmingly white, conservative, and wills towards its own undoing. And, as the girls writing essays against girlhood essays pointed out, it is dangerous when narrative conventions begin to adopt these same aesthetic principles. When we become too self-indulgent in our memories of girlhood, too insistent that we, as adult women, are girls when we are not, we should know that this is a dangerous thing, they warned.

The personal is never apolitical.

Nearly three decades prior to The Year of the Girl, a group of art school girls who made zines and formed punk bands decided it was time to riot. The Revolution Girl Summer of 1991 looked a lot different than the summer we all decided to post videos online of ourselves eating a handful of grapes for dinner or took pictures of ourselves standing inside a life-sized Barbie doll box at the movie theatre. I guess all that looks a little silly when juxtaposed with girls writing SLUT on their bellies and INCEST on their chests at sweaty basement shows, stamping around the stage like a little brat, a real brat summer.

I didn’t bring you here to debate riot grrrl, its merits and its failures. It failed spectacularly on so many levels. Like Kate Eichhorn, I like to think of the waves of feminism as a scrap heap we can pull from, always destroyed before it begins and chastised for its failings, but useful nonetheless.1 And so I brought you here because maybe you don’t know about the Revolution Girl Summer. Or maybe you haven’t thought too hard about when exactly we started to conflate girls and women and why we did that in the first place.

Because the girls that were riot grrrls knew that they were not GIRLS in the sense of the developmental stage. They were girls in the way their mothers did not want to be girls. The second wave, Women’s lib, whatever you want to call it was couched in a rejection of the 1950s version of gender and domesticity. The second wave of the late 60s and early 70s was a time when many of the women who took to the streets were doing so to reject what they saw as another time, a time of false consciousness where they had been sold a lie. And that time of false consciousness, the 50s, was, for many of them, their girlhood. And so, they hated girls.

When the young women in the 1990s decided they would never grow up, when they kickstarted this “revolution of ‘little girls’” — “adults in kidder, tantrums and rants as forms of political expressivity, juvenilia as manifesto” — they did so as a drag, a willful regression in order to invite in a cultural stereotype that was, by then, so abject as to be almost meaningless. They became girls, according to queer theorist Elizabeth Freeman, as camp, “a mode of archiving, in that it lovingly, sadistically, even masochistically brings back dominant culture’s junk and displays the performer’s fierce attachment to it,”2 a loving incantation to close a circle of pain that spans generations.

And so, Girl Power did not begin as the rallying cry of five British pop stars. Kathleen scrawled it across a zine, just like she spray painted the words Kurt smells like Teen Spirit on some bedroom wall.

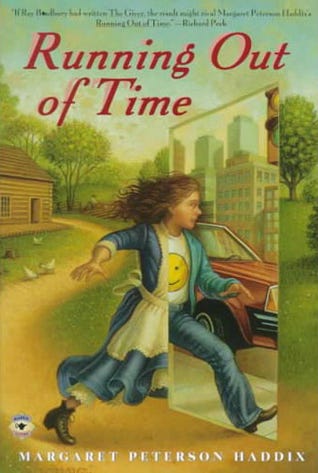

There was this book I loved as a girl. The cover of the well-worn paperback showed a girl running from one life into another.

In her old life, she wore a pinafore and you can see the log cabin she lived in with her family Laura Ingles Wilder style. Her new life is just a door, but on the others, she wears jeans and a jacket and a t shirt with a smiley face on it. She runs into a city, where there are cars and tall buildings and traffic lights, so different from where she grew up, which didn’t even have electricity.

The book is Margaret Peterson Haddix’s Running Out of Time, and if it sounds familiar to you, that’s because M. Night Shyamalan jacked the story for his movie The Village.3 I’ve never seen The Village, but in Haddix’s story, a girl named Jessie lives in a village and she thinks it’s the 1840s. Of course, it’s not the 1840s. It’s 1996. But the girl doesn’t know this until people in her village begin to die of diphtheria, and the girl’s mom is finally forced to tell her daughter that it is, in fact, 1996, and she needs to go get help.

When I was a girl, I read this book over and over and over again. I was enchanted by the idea that I was, perhaps, living a life that was one way in a world that was another way. What would it be like, I wondered, to grow up with no running water or electricity or jeans or t-shirts with smiley faces on them, and then wake up one morning to discover that the rest of the world had these things? What would it be like to walk out of my life and into a completely different one?

For a kid growing up in a strange, home-grown religious sect, access to the outside world always hanging in the balance of one man and his whims, I could not get these questions out of my head.

But now, looking over the summary of Haddix’s Running Out of Time on Wikipedia, I find it more horrifying than enchanting.

Because the girl, who must run from her dying community isn’t just running away from people who have chosen to live out of time. She’s running away from an amusement park. The people of her village, Clifton, once chose to live there. But now, they are kept there, on display unbeknownst to many of them. Every mirror a mask hiding the real world of tourists and cars and everything else, the real world that watches while the out of time world dies.

Some know that they’re looking at a dying world. Others don’t. And understanding this now, I cannot shake this darkness from the story I once loved. Because I live in a time where I am forced to bear witness to a million worlds dying through the tiny screen of my phone. And they tell me there’s nothing I can do about it.

I never feel like I’m on time. Always too late, too early.

I have talked to girls like me — the ones who tell me that they weren’t allowed to be girls while they were growing up and the ones who were girls but suffered for it and the ones who were girls but never treated as such, forced to grow up fast, fast, fast.

They write to me and tell me that my work helps them feel like they can reclaim some of that time they spent living in fear or forced out of their girlhoods. They tell me that now, as adults, they find themselves reaching back and caring for themselves as children in the ways that the adults around them at the time could not.

But many of them are scared.

Overnight, it seems, it became a dangerous time. Or maybe, it had always been a dangerous time but we decided, for a year or two, to live just a little out of time.

Girlhood is a promise, and in times like ours, that promise becomes very contentious and fraught. It becomes a playground that they use when they need and abandon when it no longer serves them. Think of the girls crowded around a desk in an office in a building and cheer while a man signs a piece of paper that says other girls like them cannot play sports with them. Or the stories of the girls conjured up to be preyed upon by nameless, faceless monsters, urging us in little corners of our social media spheres to save the children. Or the very, very real girls who bled and died alongside their fathers and their brothers in Gaza.

This is why, in times like these, we start to hate girls a little more. Because we start to see the promise of girlhood for its emptiness. We see the girls in their vulnerability, and we hate them just a little more for it. Because they betrayed us. They weren’t strong enough. They got used.

When I was a girl, my mom bought herself a doll.

The man who decided he was my father thought this was very silly and would often tell us so loudly, ad nauseam, while he ate the food my mother had made at the table she had carefully set and then cleaned up all the dirty dishes. She bought herself the doll with her own money because she wanted to play with us, my sister and I, when we played with our dolls. She liked the fun of it — that brief window of time when her girls were small and liked to play with dolls and she could join them for a little while.

But the man found this display very shameful. He told my dad so. He told us all so.

And this is when I learned that it does not matter what you do. It does not matter how good you become, or how you fit yourself into these boxes: “girl” and “woman” or neither or a little of both.

Because, and this is very important: they do not really care what you do. They do not care how you dress, or whether you feel like a girl or a woman or none of these things or some of these some of the time. All that matters to them is how they can use what you love, how you feel, what you care about against you.

They are satisfied to have you beg for their approval. They are content to keep you waiting on their recognition that yes, you are real and you are what you say you are.

This same man, the one who told me I would get raped if I dared to go to college, who shamed my mother for buying a doll with her own money, told me something else.

He said: “You walk around with your heart in your hand.”

He said: “You pulled it from your chest, still bleeding.”

He said: “You’re so cheap, you’ll give it to anyone who asks.”

And in a way, he was right. I am just a girl, who gives her heart fully, freely, to most anyone. I’m a mark, a sucker, a true believer.

But that’s what makes me so powerful.

Because when you show them your soft belly, your tender heart, it is so, so much easier to take a knife to theirs.

As always, thank you so much for reading!!! I really want to fit this into one email, so I’m not going to have room for my usual long notes but if I get the time, I’ll write some notes on this essay and publish that as a separate post. Suffice it to say, this essay was inspired by all the girls on Substack and the Internet. I’m so lucky I get to think and create and work alongside you all.

All these long think-y essays are free, so if you like my writing and want to support, you can preorder the book of essays I’m self-publishing in March and get a whole year of Internet Bedroom for FREE. Just click here to preorder :) <3

Ok that’s it. Love y’all. Stay good.

Kate Eichhorn, “The ‘Scrap Heap’ Reconsidered: Selected Archives of Feminist Archiving” from The Archival Turn in Feminism. (Philadelphia, Temple University Press: 2013), 25-54.

Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. (Durham: Duke University Press: 2010): 83, 82, 68.

Haddix sued and won and is likely the reason we will now get many years worth of Shyamalan movies as he has to keep making money I think.

The first substack post to almost bring me to tears.

Ahhhhh I’m so glad you referenced that video essay! It inspired my thought daughter essay :)