why we all want to be Joan Didion

the fantasy of this literary it girl endures online, but why?

i. false pretenses

I brought you here under false pretenses. I started this newsletter as something frivolous and now it’s something different.

This is what I love about being a writer. That I am both me and not me. That I sit down and get to touch the me and the not me and, in doing so, I somehow feel better when I stand up from my desk again.

I am performing, but I am doing it so quietly. You wouldn’t even notice.

ii. the drought

Joan Didion was born into a drought. This part is often left out of her biographical accounts, but I think it’s important. Because when you are born into scarcity and disorder, you often spend the rest of your life trying to put things right. And in the pursuit of putting things right, you can’t help but ruin a lot of other things. This is the curse.

The drought spread across the country in 1934, changing the landscape and where and how we lived, and after all this upheaval, in the last month of the year, Didion was born to a homemaker and a finance officer in the Army Air Corps. She grew up moving from place to place because of her father’s job and occupied herself with learning how to write by copying out Hemingway’s novels.

She felt like she wouldn’t be a real writer until her work saw print, and she soon got the chance, writing for her high school newspaper and then the Daily Cal, the newspaper run by undergraduates at the University of California, Berkeley, where she was enrolled as an English major. It was 1956 and, instead of getting married and settling into life as a wife, homemaker, and mother, in her senior year of college, Didion instead entered an essay contest sponsored by Vogue. The essay won her a position as a research assistant at the fashion magazine, and Didion would spend the next decade in New York City, working her way from research assistant to associate feature editor at Vogue, all the while writing and publishing her own essays.

“You know those early essays,” Hilton Als writes in his posthumous assessment of Didion’s career. “[Those] essays that are fetishized time and time again, mostly because they’re read wrong—as a kind of articulation of, and nostalgia for, what is now called white-woman fragility.”

As Als tells it, the arc of Didion’s writing and career is one that moves from wishful thinking to direct confrontation with the system that let her ever dream in the first place. Didion showcases a directness and restraint in her voice that cuts away at all fantasy and pretense, hardly buying into the lie that the pain of white women is somehow interesting.

But even though she is often looking so directly at the thing she is writing about, some things slip between the sentences. Elision becomes a dangerous trick in her essays, a trick you would barely notice. You might not even see her in the woman standing naked on her balcony, having a nervous breakdown in “The White Album” — one of those essays that we do fetishize. But she’s right there, hidden in plain sight.

iii. the literary it girl

Earlier this year, I wondered if It Girls could even exist at all anymore.

Being It requires a certain degree of unknowability, unreachability, unavailability. It isn’t just about the allure of beauty or sex appeal or social mobility. Rather, to have it is to have a coolness that puts the girl just out of reach, as if she came down from another planet entirely and plans to return there soon. And I didn’t see how that was possible in an era in which, as Claire Dederer put it, “Biography…falls on your head all day long” in a deluge of posts and threads and tweets and videos that show us your insides and out all the time in an endless scroll.

The literary it girl, however, is a certain kind of persona that seems specially designed to deal with the ever more pressing demands that we should see everything about a person’s life and understand it. We are a group who are particularly skilled at showing you exactly what we want you to see, of casting a spell over you with a very crude instrument.

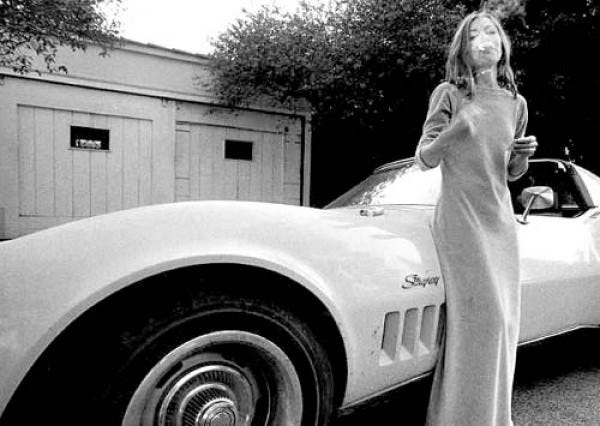

For the hundreds of pages she wrote and published across sixteen books and a handful of plays and screenplays, I still can’t fathom how Joan Didion ended up following Jim Morrison into The Doors studio sessions. Or how the houses she and her husband rented in and around LA came to be filled with movie stars and comedians and entertainers. Or why she was buying clothes for Linda Kasabian while she was on trial for murder. It seems incongruous for a woman who was known as “the wife of a writer” and not the writer herself, who adopted a baby she renamed after her favorite children’s book, who subsisted mainly off of cold Coca-Colas and cigarettes, to suddenly be partying on the weekends with rock stars and finding a needle and spoon on her daughter’s nursery floor, left by a party guest. But there she is.

I have read a number of essays on this platform and elsewhere that find young, often femme writers confessing their desire to be like Didion. “Young life: Why I’m desperate to be a literary It-girl,” reads the headline of one essay in which the writer confesses that she is trying to “cultivate” a “new aesthetic” inspired by “image after image of hot women posing nonchalantly with books, splayed out on beach towels with their faces obscured by the likes of Sylvia Plath, Joan Didion and [Eve] Babitz.”

The image of the writer is what’s important here, not the writing itself. But notice how the aesthetic of the literary It-girl is designed to conceal: books placed over faces so you can see the body but not the woman herself. The authors we choose stand-in for the self we won’t show you. And we hardly need their words to do that.

We are meant to disappear, to get lost between the lines so we can watch you. But now that you require our image to be everywhere — always visible, documenting our movements, pinpointing our locations — it feels harder and harder to get away like that. Every time I post online, I feel like I’m pulling off some kind of heist. What I show you is so calculated, so controlled because I still need to be able to fade into the background, to observe you, to see your heart before you see mine.

iv. the list

I want what she has.

A big, beautiful house on the ocean.

Thighs that don’t touch.

A list taped to the back of a door that tells me exactly what to pack as a jet off to my next writing assignment.

This is the fantasy.

There was one summer in my early 20s where my life was absolutely coming apart at the seams, and every time I left the state, I would send a screenshot of Joan Didion’s packing list to my friend. I wanted my life to make as much sense as this list did. But your life doesn’t really cohere into a clear picture until about a decade later. It still might come apart again and again, if I’m being honest.

I told that same friend I was writing this essay about Didion and persona and all that over the phone that decade later, and she went, “Oh my god The List.” “The List,” I echoed, as her baby babbled and I watched the dinner I had just made my husband and I grow cold on the counter.

It does not escape me that Didion wrote this list for herself because her life was spinning out of control at the time. Baby and husband at home, she found herself on the road to do her reporting. I’ve done the same thing. My urge to run, a genetic predisposition, comes with its warning signs: summers spent on the road without my boyfriend; work piling up so high I barely have time to eat. What was she running from, I wonder, when she wrote this list that would allow her to get out at a moment’s notice?

Caught up in the lives we were choosing to stay in, my friend and I wondered what would be on The List if it was written now. To carry: 1 vape and cartridges containing both weed and nicotine. Stop, stop, we giggled, pouring out the contents of our purses and all the absurd, useless shit we’ve kept in there over the years.

v. the notebook

I started this essay in a drought.

I had come back to my house in Ohio and found that the leaves were turning at the end of August from the heat. It reminded me of how my godmother once stared at me through the haze of an opioid — I’m still not sure which one — and told me that one day Ohio would be a desert. Her eyes were glassy and I thought she was just high and didn’t know what she was saying. Now I’m not so sure.

The first essay I ever read by Joan Didion was “On Keeping a Notebook,” one of her personals, short essays she wrote for different magazines reflecting on the little things that grate at the back of one’s mind. This one she published in 1966, the same year both my parents were born, and in it she recounts how she was given a Big 5 notebook by her mother and told to entertain herself by writing her thoughts down.

For Didion, keeping a notebook and recording her thoughts is not a natural thing to do, and she spends much of the essay wondering at this strange compulsion to document what she sees as she passes through her days. “Why did I write it down?” she wonders. “In order to remember, of course, but exactly what was it I wanted to remember? How much of it actually happened? Did any of it? Why do I keep a notebook at all? It is easy to deceive oneself on all those scores.”

It was my English teacher who gave me this essay, my first from Didion. She assigned it and then read aloud “Goodbye to All That,” which is Didion’s farewell to New York City the next day in class and my life was changed forever. This is what I tell people now when they wonder why they should keep writing. You don’t know what can happen, I say. You don’t have any control over how your work will move and change people. You’re selfish to think you do.

Of course I had been an itinerant diarist since I was a child. All my notebooks from then until college are locked in a travel trunk that was once my great-grandmother’s. And then something happened to me and then I didn’t keep a notebook anymore. I still don’t.

For her part, Didion saw her notebook as an archive of all her selves. She writes: “I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not.”

But I did not want to sit with her, this girl who was so lost and confused. This girl whose boyfriend yelled and screamed at her. This girl who thought she was cursed, a curse that had begun before she was born and traveled down bloodlines until it finally found her and then spent its days suffocating her.

I don’t like the look of her.

In the last moments of that girls’ life, she was sharing an apartment with another boyfriend, the one that would become her husband, and he was making a book. The apartment was very small, really one long hallway with a bedroom attached to it, and every night, it would fill up with artists who were helping him make his book.

One night, one of the artists looked up from his work and said: “You are the one who watches. You are the one who will be here still when all of this is gone. You’re the one who will remember.” And she cried. Because she didn’t want to be the only one left.

To endure it and survive and then arrange it all in a way that makes sense. That is Joan Didion’s legacy. And that is beyond fantasy.

As always, thank you, thank you for reading! I am still floored by the support I got on last month’s essay. I have two more longer essays to share with you this year, so if you enjoy this sort of writing, why not stick around?

I wanna take a moment and shout out a few other pieces on Joan Didion, the Literary It Girl phenomenon, and our visibility online as femmes and creatives that I absolutely love, that informed this essay, and that I recommend as further reading:

on the aesthetics of intellectualism online and how that’s tied to the literary it girl in “I’m smart and I need everyone to know it”

‘s fantastic pair of essays “oh so you’re a thought daughter now? should i call Joan Didion?” and “not everyone can be an ‘it girl’”

has a great interactive series that dives deep into Didion’s essay collection “The White Album” and you can read the first one here!

’s primer on Literary It Girls, “in search of cool”

and last but never least, ’s “am I hot enough for a good life?” which considers the price of accessing visibility and success

Thank you again for reading. if you don’t want to listen to “California Dreaming” to close out this essay, you can listen to “How to disappear” by Lana del Rey.

Didion says herself in the introduction to Slouching Towards Bethlehem that even those who praised her work consistently "missed the point." That trend seems to be continuing for her posthumously, with most turning to her primarily as an aesthetic icon. Sure, she was chic, but she was also an incredibly brilliant cultural critic who, from what I've read of her, would loathe the infatuation that e girls have with her today. The commodification of her persona as an aesthetic or lifestyle icon feels ironic, given her body of work was often about peeling back the layers of shallow or performative culture. She dissected the emptiness behind glamour and coolness, so it’s interesting (and a little tragic) that this is how she's remembered by some now. This was a fresh take on her. Thanks for posting!

Rachel this was incredible. Internet Bedroom makes me want to start writing again